New research from the Policy Studies Institute (PSI) shows that only a quarter of English primary school children are allowed to walk to school alone – yet in Germany, three quarters are. It is easy to think that the decline in children’s freedom to play out of doors and get around on their own is an inevitable side effect of modern life. That is why international comparisons are so valuable: they can show us how things might be different.

The Germany-England comparisons are rightly grabbing the headlines; yesterday’s Sunday Times ran an exclusive news story (mostly behind its paywall) on the findings, and it was also picked up in the Daily Mail. [Update 16 Jan: it was also covered in the Telegraph and Independent.] And the figures do make striking reading. The study shows that German children enjoy consistently higher levels of independent mobility across a range of ‘licenses’ (including travelling to and from school unaccompanied, travelling by bus and by cycle) and a range of ages.

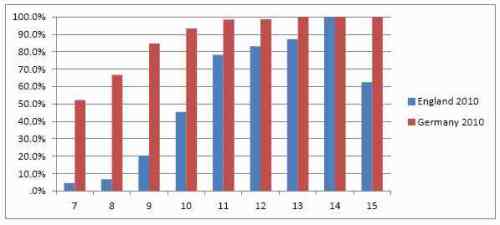

Percentage of parents reporting that their child is allowed to travel home from school alone, by age, England and Germany

But the research has more intriguing stories to tell. For example, it finds that the independent mobility of German children has also declined in the last 20 years, like that of their English peers – but nowhere near as much. In fact, if we were to wait for the independent mobility of German primary school children to fall to the level of their English peers, we would have to wait another 60 years, on current trends.

The report makes a strong case for the importance of children’s independent mobility. It is clearly a factor in children’s physical activity levels, and hence their levels of overweight and obesity. It is also relevant to children’s health, well-being, and more fundamentally to what a good childhood looks and feels like. It is revealing that research last year from the Children’s Society found that freedom of choice was the single most significant factor in influencing children’s overall levels of subjective well-being.

The study itself has only limited insights to offer about why English children’s independent mobility has fallen so much over the last forty years, and so much more than in Germany. The Sunday Times and Daily Mail pieces take the easy option [update 16 Jan: as does the piece in the Independent] by pointing the finger of blame at English parents, with their use of the phrase ‘cotton wool kids’. My own view is that it is differences in car culture, not parenting culture, that are key – as I have argued before.

Many German cities have efficient public transport and safe, popular walking and cycling routes, along with generous, well-managed green spaces. Take for example Vauban, a new neighbourhood in the Southern German city of Freiburg, which I visited in 2005. The housing, road network and parks and open spaces are thoughtfully laid out, so that almost all homes look out on some attractive public green space. Cars are parked away from houses and apartments, while an efficient tram system means fewer families feel the need to own a car at all. The front streets are designed along ‘home zone’ lines to be sociable spaces where the car driver is a guest. It is no wonder that families are queuing up to live in the area.

The PSI report, which has in effect been four decades in the making, adds another generation of data to its seminal One False Move study published in 1990. The result is a dataset that is of unique value in researching children’s independent mobility, as I know from having been on the project’s advisory group since its inception. Not only do we now have baseline and trend data from England, together with a set of comparable baseline data from Germany. Now, for the first time, we have time trend data from both countries.

One of the PSI study’s co-authors, Mayer Hillman, deserves a special mention. A longstanding and uncompromising policy analyst and campaigner on environmental issues, it was Hillman who realised over forty years ago the significance of children as an indicator of the quality of the habitats in which they live, just like salmon in a river. His work has been a big influence on my own thinking.

One of the PSI study’s co-authors, Mayer Hillman, deserves a special mention. A longstanding and uncompromising policy analyst and campaigner on environmental issues, it was Hillman who realised over forty years ago the significance of children as an indicator of the quality of the habitats in which they live, just like salmon in a river. His work has been a big influence on my own thinking.

The report holds back from making detailed policy recommendations, in part because a more extensive set of studies, comparing children’s independent mobility in 16 more nations, is in the pipeline. Nonetheless, its 248 pages are well worth studying in detail for their insights into the changing nature of childhood. I plan to revisit the findings, and would be interested to hear your views on their implications.

I share your view that car culture and car dependence is ultimately to blame for this!

Hi Tim, this is a really interesting comparison. Having grown up in Switzerland we were afforded much the same independence as children in Germany, although I couldn’t comment on stats. This continues even today: my 5 year old nephew walked to and from Kindergarten independently, sometimes buddied up with a neighbourhood friend. Kindergarten children walking to school wear a V-shaped, high-viz “Triki” (not a full vest) so that the public can see they are on their way to and from school. Kindergarten children also have traffic safety training at school (usually delivered by a policeman from the community) that covers everything from crossing the road safely to IDing and understanding the characteristics of their walk to school – this also involves being taken out to a road and practicing. This kind of empowerment and independence at an early age can have longer-term, positive effects on maturity, self-esteem and confidence as well as risk management abilities. I would add that this is supported by a cultural engendering of walking/taking public transport over taking the car, taking/being given responsibility and also of prudent planning decisions.

Gabrielle, Elana: thanks for your comments. Elana – others have told me similar anecdotes of very young (pre-school) Swiss children walking to and from kindergarten without adults. Indeed I’ve been told that parents who *do* accompany their children to kindergarten are looked down on!

It’s an interesting balance between paranoia and genuine concern as regards the roads…

I was once called by my daughter’s school to say she’d been given a “yellow card” for disappearing out of the school with a friend without asking just before the morning bell went. Fair enough, I thought, they can’t be expected to be responsible for people who disappear off to places nobody knows about, but it turned out the “problem” was not disappearing but that they hadn’t used the school crossing patrol and had crossed the road by themselves. That over a not actually very busy road that she’d cycled along to get to school in the first place. We’d showed both our kids how to cross rather busier roads independently long ago, so it does seem that while we need to be concerned about traffic we also need to be realistic about how to deal with it, and if we are it needn’t cramp our style quite so much as it does.

I just sent the link to the playground pics to my local parks director. I hope it at least sparks some imagination!

Pingback: Big adventures! « Love Outdoor Play

Peter – the question of schools’ role in children’s school travel is intriguing. It’s certainly an issue in the USA and Australia. But I can’t see that it’s any business of the school – surely it’s for parents to decide (as I have argued here). I’d love to know if German school restrict children’s travel.

German schools have no legal say in telling parents how their children travel to school, though they certainly give advice. Children are insured when using the shortest safe walking route and don’t lose insurance when injured while on an age-appropriate detour.

Thanks for this comment Peter. Can you explain what you mean when you say ‘children are insured’? Is this to do with health cover in the event of an accident?

Most children with have health care insurance one way or another. It is not that easy to drop out of insurance, though some adults actually manage. But as soon as you are on social benefits, you are usually covered. But that aside, school way insurance goes beyond usualy health care insurance.

* Physicians fees and hospital fees

(Yes, usually covered by health care, but they can charge the original culprit, in some cases, to recover costs. Some for some other points, I’m not an insurance expert, I’m basically just translating a list here. ).

* Drugs and other remedies.

* Rehab therapy

* Care at home or in homes, if necerssary.

* Private schooling in case of longer hospital stays

* Replacement of destroyed aids, like broken glasses.

* a pension, when there are still major impairments after 26 weeks after the accident.

* „Verletztengeld“ (“injury money”), a pension of 80% of a parents income if said parent has to stay home to take of their injures child under 12.

This is for all accidents, most importantly the self-inflicted ones. In case of a car accident, the car’s insurance will pay about the same. In case the car/driver wasn’t insured (which is illegal, of course), a fond managed by the insurance companies for these occasions will step in.

And yes, sometimes parents will still have to fight for their right in case of special therapies or remodel their home to accommodate their child, if the accidents was grave and had severe effects.

Hi Tim, Glad to be the first!

Interesting reading I think it reflects how far advanced the German market was 10 years ago. They did not have the same need as we did to catch up on the need for risk or the importance of nature in play. Not that it was all paradise over there, but there was more awareness of the need in pujblic places for children’s space, nature and risk.

What is sad is that they are suffering the same trends as us and I am conscious of the number of people I meet and hear from on the continent who make the same comments. Clearly there is still work to be done on both sides of the water!

Wendyww – tell me if you get any results. Robin – nice to see you here. I think that the trends you point to are probably going to happen everywhere in the richer nations, because to some extent they do reflect the consequences of affluence. But we can mitigate them, as the Germans, the Dutch and the Nordic nations have shown.

I grew up in Germany and find this study of great interest. My first thought was that it’s also not comparing like with like in so many ways. First up, a school child is no younger than 6 in Germany. School starts at 4 years in England. I was almost 7 when I started school in 1977 and I did not walk to school on my own in the first year, I did from when I was 8, with a group of children from my street (it was a long walk without any major roads). Secondly, cycling is a whole different ballgame in Germany. There are cycle lanes everywhere, often set apart from roads with a bit of green space between road and cycle lane, they are not shared with buses, and driving instruction training makes sure that car drivers watch out for bikes. Cars are responsible for the safety of bicycles and pedestrians. Also, everyone cycles in Germany, the very old, the very young and everyone in between. If I compare my walk to school with my daughter’s, all I can say it’s not comparable. I walked through fields and a traffic calmed residential area, we walk across a major road and have pavements that are extremely narrow during the school run. The physical set up/infrastructure is not the same. At the same time I would be happy to let my daughter walk it on her own from when she’s 8 – which is where the cultural difference kicks in: School, peers, even my family would think I’d be putting my daughter in danger. So I probably won’t let her do it, but that’s just a contributing factor and the last barrier to an independent school walk. So I totally agree with your take on it, that it’s not all about cotton wool kids but city planning that puts cars first.

Tim this is really interesting and is of even more interest because the Australian Bureau of Statistics (http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4901.0) have just released research on Australian children and the decrease in physical activity and significant rise in in screen based activity (2006 – 2012). I think our experience is very similar to the UK – increasingly children are being removed from the outdoor world, we create playgrounds that entertain, but don’t allow children to engage, or change the play space. Adults have become helicopters over children – watching every move and ensuring that their is no idle time, we fill up all the available time with planned activities.

Other issues that the ABS report finds is that children are reading for pleasure less than they were 6 years ok.

I’m not sure it’s just culture, it may also have to do with distances to school. In the US town where we live, there used to be 10 elementary schools and most kids walked, now there are only 5 so the distances are greater. I don’t know what it is like in the UK, but if they have also gotten rid of neighborhood schools in favor of consolidated bigger schools that may be part of the reason. We live in walking distance of the school and all the kids from age 7 or 8 walk alone, younger siblings often walk with older children. But of course, many kids are too far and are driven by their parents.

Cartside, Neville J, suburbanmama – thanks for the comments. Interesting to read your confirmation of the difference in walking and (especially) cycling infrastructure, Cartside. Though I think the PSI study found quite low levels of cycling – possibly a reflection of the areas surveyed. I will check out the Oz statistics – as followers of my blog know, I have done quite a lot of work in the country and it seems to me there is a great deal of interest in childhood, and some momentum behind the idea of reshaping public policy to improve children’s levels of physical activity and independent mobility. Suburbanmama – i am sure you are right that larger schools – and also changing policies on school admission – are a factor. But the PSI study found differences in a range of licenses, not just the school trip. So other factors are at play.

Nice article, Tim.

I agree, and I think that a lack of independent mobility is one of the most important issues facing children and young people, and not just for reasons of health and fitness. That great film ‘Playing Out’ by Ian Duncan, an exploration of the journey from home to school and back again, showed how important independent mobility is for social reasons too.

Problem is, although there are practical reasons for the change (traffic, changing status of local schools, urban design) ultimately it comes down to adult attitude – parental fears and a lack of consideration by designers and policy makers. Tough one to battle.

I think for me it is also a question of respect and entitlement. It’s about choices and being able to make them because independent mobility is a well-being issue, and one of the big ones, but until our general attitude towards children’s lives changes we won’t see the practical changes we need to counter this one.

Marc – thanks for the comment, and good to see you here. I agree that adult attitudes and priorities are at the root of the problem. However, there are lively debates going on about the shape of cities, about transport and about the design of new neighbourhoods, and some of those involved are arguing for more child-friendly approaches (though sometimes they don’t realise it).

Tim

Yes, I accept the point that there are voices out there that are on our side on this one, and thankfully there always have been. The question is how to we move from supportive voices to physical reality.

I cite, for example, the option that residents on the Ocean Estate in Tower Hamlets were given over the redesign of their housing blocks by the New Deal for Communities Programme: in the centre of your new blocks would you like, a) a community playspace or, b) a car park. Guess which they went for?

We will score our greatest success when the positive views are not just lone voices but the norm. So more of this kind of thing, Tim (Father Ted there, do you see what I’ve done?) so more blogging, more debate and then LOTS of action, please.

Careful now!

I wonder what the stats would show in the US suburban communities. The US is so behind and has so much to learn from this. Thanks Tim. Maybe you could share this also on the International School Grounds Alliance FB page.

Thanks for this Ora. Have done. Any US readers know any stats on children’s independent mobility? Sadly, I don’t think any researchers from the country are involved in the bigger study I mentioned.

2 main indicators of a society’s overall health are the levels of freedom children of all ages exercise within a nurturing environment and the level of inclusion elders enjoy within a community. If a hard look is taken at North American society, children are rarely heard from or seen on city streets and parks at any time during a given year whereas, after the age of 70 or so, elders rarely partake in communal activities other than those found in “their” homes for the aged. As indicators, therefore, is it reasonable to assume that the well being of North Americans is rather precarious in both areas of physical and mental health?

Bernard – good to see you here, and I’m finding it hard to argue with your position.

HI… I am German also, living in the US since 18 years and having raised three children here.. I very much missed the German way of being able to let my child go outside by himself, or walk anywhere from our home. I find the infrastructure very much car oriented, distances, as well as property sizes considerably larger, thus there is hardly any bike paths, but 80% large roads. Hey, even a small town has double the width roads as you would find in any German town, so traffic is much moire unpleasant, the sight is usually anything but inviting if I comare it to bike paths I know from back home. Same for distances with everything just soooo stretched out. I do see very gratefully a movement here in the US by archtiects, trying to rethink communities and how to build them more “inhabitants friendly” Car joy is not everything.. community is built by people passing each other in the streets, by NEIGHBOORhoods, not “stranger”hoods.. I never felt so diconnected from other people as I do here in my life in the US. and I do believe the way communities are built plays a BIG role in this.

Also having more green spaces everywhere, planting trees along roads, ( the green lung has always been a respected issue in German city planning) reducing distances between people, or at least creating social areas within any of these neighborhoods, and not only schoolplaygrounds, how about a playground, WITH nature: shrubs, trees, boulders, treestumps, etc, incorporated in all those estranged neighborhoods, it would draw people back out and together, alas help overcome the hurdle of keeping your child from going by itself into the “unknown” .

Pingback: The sorry state of neighbourhood design in America: a mother writes | Rethinking Childhood

I want to point out that it goes beyond walking to/from school: My wife is Austrian and was commenting just the other day how elementary schools in Austria, even today, teach children the practical and social aspects of shopping at a store (asking for items, asking the price, counting out the money or expecting change). The underlying assumption is that kids as young as 7 and 8 get sent to the neighboorhood store or bakery by themselves to get needed items, such as fresh bread in the morning. Of course, Europe has more walkable neighborhoods and neighborhood stores (and worthwhile bread and pastries) that make this possible. But it’s not just the aspect of being possible, it’s the idea that it’s expected, and that schools teach the skills. It’s also the idea of giving children tasks and responsibilities, not just walking home from school.

Pingback: German children enjoy far more everyday freedom than their English peers | Mark Pack

Reblogged this on Carping From The Side Lines – Iorek's Blog.

I haven’t yet had a chance to read the report yet but that looks like an odd dip at age 15. We did a similar analysis on 2006 data from schools over the country and in relation to Hillman’s earlier research to provide a longitudinal perspective (see breaktime.org.uk/Travel%20to%20School-ResearchBrief1.pdf). One of the findings that intrigued me was that girls’ level of walking to school increased between late primary to early secondary but then declined again in later secondary. I took it to mean something along the lines of girls enjoying their increased autonomy but then possibly becoming more lazy in later secondary school – though equally it might be that parents become fussy about their daughters again.

Ed, thanks for the comment, and the link (which I have hyperlinked for you). The full PSI report says that the age 15 figure is ‘anomalous’ and due to ‘small sample size’ (p.165) – though I cannot find the raw data. Your own study – which from what I can see broadly confirms PSI’s – makes some useful points about the implications for schools. I strongly concur with your closing remark: “A greater effort could be made to locate primary and secondary schools at the heart of the community and to provide opportunities for children to use school playgrounds and playing fields out of school hours to enable them to socialise, play and explore the world relatively freely with adult support and monitoring, not control.”

Hi, I have been living in Germany for 6 months now with my German wife and 2 1/2 year old son. I have lived in Australia all my life and worked with school age children for the past 20 years in Outdoor Education. Ironically just yesterday at lunch with some German friends I had made this observation after seeing dozens of children of all ages walking to school, waiting for busses and being very self sufficient and happy. The clincher for me was that it was dark, minus 5 Celsius and snowing. Something as an Australian I had never seen and would never see in Australia. A fine, warm daylight morning wouldn’t see that many children getting themselves to school independently in Australia.

This article certainly resonates with me as I see my role in outdoor education sometimes as simply to introduce children to the simple pleasures of self sufficiency. Something people of my age, with a farming background and with supportive but realistic parents took for granted when growing up.

This tide needs to be turned! If a country with the reputation of outdoorsy types etc like Australia is really no better than any other in sheltering thier children to extremes, then what a mess we will have if this trend is found to be common globaly.

Regards

Tony Miller

Thanks for the comment Tony. You are right to see the links between your educational goals and children’s everyday freedoms. The problem in Australia is that the way your towns and cities are designed means it is very unlikely that children will be able to get around unaccompanied. I have visited Australia a half-dozen times or so in the last few years, and what has always struck me is how car-dependent the culture is.

All interesting stuff which perhaps shows how deep cultural norms go even over fairly small actions. 15 years ago when my children were going to school it was easy to walk (Sea promenade) and hard to drive (two right turns and school down cul de sac) – but people did still drive their children to school (less that 1/2 mile). Though I think that part of their argument would be safety for the children I think that it was also partly everyone getting out of the house together, parent going to work after dropping off children – whether this was to be with the children for as long as possible or not trusting them in the house alone …?

Thanks for the comment Ben. Your comment highlights the fact – shown by the PSI study – that in England, the biggest falls in children’s independent mobility happened in the 70s and 80s. You are right of course that individual parental decisions about the school trip are shaped by many factors, including convenience, the fit with other trips, and safety concerns of various kinds. But I would still argue that the built form of neighbourhoods is the single most important factor.

Pingback: Alleine auf dem Schulweg… | Die wunderbare Welt von Isotopp

Pingback: A century of rethinking childhood | Rethinking Childhood

I grew up in Germany and my daily walk (no adults needed) to primary school and back home with my sisters was a wonderful experience (we had long walks and crossed many roads) …I live in London and it “hurts” me that I cannot give this experience to my three daughters who all visit the primary school ACROSS the road! My sister’s children (growing up in Germany and Holland) enjoy their ‘freedom’.

Elisabeth

Thanks for the comment Elisabeth. Let’s hope the powers that be recognise the need to make it easier for children to get around on their own, and improve conditions for walking and cycling. There are some positive signs this is happening in London – for instance with the investment in cycle paths.

I’m german and I have to say, that as a kid I had way more freedom than only walking to and home from school alone. At the age of 8 I was allowed the whole suburb and the woods behind and I have to say it was such an adventure for me and my friends to roam around and it was like a big playground for us and almost everyday there were new things to discover.

Summer 2006 it was a cool time.

Thanks for the comment – clearly your experience fits with the broad picture; I doubt many 8-year-old English children would have enjoyed that much freedom in 2006. You are right to emphasise that this is about more than just travel to school. Just to add that the report looks at a range of ‘everyday freedoms’, not just the trip to school.

Pingback: Last kindergarten in the woods? | Rethinking Childhood

Pingback: German children enjoy far more everyday freedom than their English peers