Let’s say that, like me, you are signed up to the idea that we’ve become too overprotective and anxious about children in their play. What language should we use to make the case for a better approach? In particular, does the word ‘risk’ – for instance, in the term ‘risky play’ – help or not?

![]()

UK play advocate Adrian Voce – my successor at what became Play England – has questioned the use of the term ‘risk’. While recognising the progress that has been made on the place of risk in play, he says:

Although ‘risky’ and ‘adventurous’ are, in a sense, synonymous, the latter word has an unarguably more positive meaning. It also captures much better the essence of children at play – wanting to push the boundaries, test their limits and, sure, take some risks – but in the pursuit of fun and excitement, not the reckless endangerment that the term ‘risky play’ can evoke… ‘Risky’ cannot be the most appropriate word to describe the opportunities and environments we want to provide for them, or the practice we adopt in doing so.

His concerns are echoed by American teacher and blogger Kim Allsop, who said in a recent post “please, can we stop talking about risk? Instead, let’s talk about adventure, preparation and trust.”

I hope we would all agree that we need a more balanced, thoughtful approach to the unpredictability that is such a central part of children’s play. We need to recognise the value of a degree of freedom, choice and autonomy. And we want to get well away from where we were in the 1990s, when the word ‘play’ had the word ‘safe’ inserted before it by default.

We need to accept that when children play freely, the outcomes are uncertain. In other words, we need to accept real risk. Of course, this does not mean accepting recklessness – but no-one is saying it does.

Accepting uncertainty of outcomes – accepting risk – means accepting that sometimes, children will make mistakes and get hurt or upset. In fact, we are not doing our job properly if they do *not* sometimes make mistakes and get hurt or upset (thank you Teacher Tom, who has grappled with the language here more than once).

The acceptance of risk is not just a detail: it is the single most important step that we are asking the anxious to take. Using the word ‘risk’ is of value precisely because it faces head-on the possibility of adverse outcomes. (Back in 2002, the milestone Managing Risk in Play Provision position statement strikingly stated “it may on occasions be unavoidable that play provision exposes children to the risk – the very low risk – of serious injury or even death.”)

The acceptance of risk is not just a detail: it is the single most important step that we are asking the anxious to take. Using the word ‘risk’ is of value precisely because it faces head-on the possibility of adverse outcomes. (Back in 2002, the milestone Managing Risk in Play Provision position statement strikingly stated “it may on occasions be unavoidable that play provision exposes children to the risk – the very low risk – of serious injury or even death.”)

Avoiding the word ‘risky’ and instead using ‘adventurous’ or ‘challenging’ is having our cake of uncertainty and eating it. The implied message is ‘your child will have adventures – but don’t worry, nothing will go wrong.’

There are lessons from the knots that ‘adventure activity’ folk have tied themselves into for decades over risk and safety (as Simon Beames argues in his recent book Adventurous learning: A pedagogy for a changing world). A similar fate befell many British adventure playgrounds through the 1980s and 1990s. The adoption of the word ‘adventure’ did not appear to insulate them from the rise of excessive risk aversion.

That said, I do have reservations about the term ‘risky play’. I recall first coming across it when reviewing Helen Tovey’s 2007 book Playing Outdoors: Spaces and Places, Risk and Challenge. As I said at the time, it conjures up unhelpful notions of ‘doses’ of ‘risky play’ as a kind of antidote and add-on to overprotective, intrusive supervision the rest of the time. But I would hope that thoughtful practitioners would be alive to that danger.

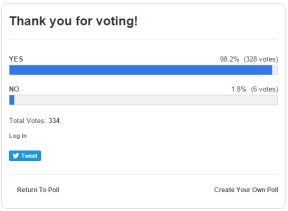

As for the views of parents, the press or the public, I am wary of speculating. I do have one (admittedly unscientific) piece of evidence that these audiences may not find the R word as off-putting as some seem to think. It comes from this news article. After reading it, 98% of those who voted in effect voted ‘yes’ to elements of risk in playgrounds.

Even if in some contexts, the R word is a step too far for some – and it clearly is – language changes, and the meaning of words evolves. And sometimes, that happens precisely through choosing words that question and confront existing values. Just look at how the LGBT community has reclaimed the word ‘queer’.

The Norwegian early years academic Ellen Sandseter is closely associated with promoting ‘risky play’ and has worked up a research definition of the phrase. Her contribution to this debate parallels my views on the merits of ‘risk’ as against ‘adventure’ or ‘challenge’.

She also makes the sound point that context and culture are important, and reasons to be wary of general statements about language. I wonder, for instance, whether the USA might be one place where the R word is a hard sell.

Having said that, let us look globally at play advocacy over the last decade or so. While there are not many causes for celebration, one of them is surely around risk.

Almost wherever you look, more balanced and thoughtful approaches are emerging: in playground design, risk management, playwork practice [pdf link], regulatory positions, equipment standards, outdoor learning, school grounds, parenting debates, accident prevention perspectives, children’s rights [word document link], visitor attractions, playful public spaces – even in in the courts.

This global progress has been underpinned by clear messages about what freedom, choice and uncertainty mean in children’s play. They mean risk.

I came across two examples in recent months. The first is from Sweden, and the Government guidance for a £50 million investment programme in school playgrounds. Its first substantive section is headed “necessary risk-taking.” It states: “Open spaces for children and young people should be planned and designed to promote children’s opportunity to seek excitement in their play, even where this may involve some risk taking” (according to Google Translate). The second is from the Netherlands, where Dutch play advocates are meeting next week to discuss ‘risk and resilience’.

I came across two examples in recent months. The first is from Sweden, and the Government guidance for a £50 million investment programme in school playgrounds. Its first substantive section is headed “necessary risk-taking.” It states: “Open spaces for children and young people should be planned and designed to promote children’s opportunity to seek excitement in their play, even where this may involve some risk taking” (according to Google Translate). The second is from the Netherlands, where Dutch play advocates are meeting next week to discuss ‘risk and resilience’.

My own work on risk with parents, educators, playworkers and decision-makers over the years has taken me across the UK and to mainland Europe, North America, Japan and Australasia. The impact of this work is for others to judge. But what I can say is that clarity about risk – that it means real uncertainty of outcome – has been a central and indispensable theme.

For proof of this, take a look at the tag cloud on the right hand side of your screen.

Photo credit: Lunchtime at Beacon Rise Primary School, Bristol (an OPAL Platinum school) during my visit last week.

Reblogged this on Play and Other Things….

Hi Tim,

I’m glad my piece has provoked a response from you as I think a debate will be helpful. I am planning a series of blogs on this theme and will take up some of your points there, but I must first correct your assertion that I have ‘questioned the use of the term ‘‘risk’’ ‘.

My piece is very clear that it is the banner ‘risky play’ that I think is inappropriate, not the use of the word ‘risk’. ‘Risk’ and ‘risky’ are not the same word and I have never shied away from discussing risk in play, as such (as you know, it was my initiative to commission the first edition of Managing Risk in Play Provision: Implementation guide, for example).

best, Adrian

Thanks for this Adrian. This is a valuable debate, and I look forward to seeing your posts. My post was not solely prompted by yours, of course. Another hook was to a post that argued against the noun, not just the adjective (if we are to get grammatical). There is a lively debate going on in Canada, for instance, around language and terminology, which my post aims to contribute to.

I am grateful for your clarification. The differentiation of your views around ‘risk’ versus ‘risky’ was not clear to me from your piece. I have reservations about ‘risky play’ too, though my concerns appear to be different to yours. However, can live with it, not least as a provocation. I remain unconvinced that the terms ‘adventurous [play]’ or ‘challenging [play]’ are adequate to the task of building a more balanced, thoughtful approach to risk in play.

One further minor point: you state in your post that the term ‘risky play’ does not appear in MRPP:IP. In fact it appears a couple of times, albeit modified by the adverb (grammar again!) ‘potentially’.

Thanks Tim. In the first edition? I thought not, but could be wrong.

Yup. Pages 15 and 76, says Adobe Acrobat’s search function.

And just to add that:

1) as I say in my blog, I think language is important. In common parlance, I think the word ‘risky’ has a negative connotation; describing something best avoided. I think the growth of its use in the play world has a different meaning to this, but leaves us open to misunderstanding; and

2) I do have other concerns about the term ‘risky play’, perhaps closer to yours; to do with adult agendas for children’s play and the design of space prescribing how children will use it. More on this in my blog.

To quote Woody Allen (from before we had to hate him)

“What am I, chopped liver?

http://teachertomsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2016/06/the-inherent-risk-of-risky-play.html

3 comments:

arthur battram said…

Looks like the attempt, by a few of us in the UK world of play, to avoid calling it ‘risky’ and instead call it ‘challenging’ has failed. I think only Peter Gray, myself and Rob Wheway, use ‘challenging’.

We don’t call mountaineering or bungee jumping or MTBing or soccer, ‘risky play’. All are play, all are risky. These days you see disclaimers at the various venues talking about risk, but we don’t think of them as risky as such, and they aren’t described as such. You won’t see the ‘Poughkeepsie Risky Mountaineering Club’ advertising on local TV.

When we label children’s challenging activities ‘risky play’, we are colluding with fearful parents and risk-averse authorities and the industries that prey on them, like lawyers and insurers.

I’m disappointed that you, Tom, a major advocate for the value and importance of play, have missed the opportunity to ‘rebrand’ a vital part of childhood in a more positive and affirming way.

Life is risky. Walking down the street is risky. If you are a naive teen, you might take a risk and walk home through a ‘bad’ area. That teen obviously needs to improve their thinking about risk, says society, and equally obviously, as we grow up we learn to assess risk.

IMHO, the issue is not ‘risk’, it’s challenge. To decide if I’m up to a challenge, like a scary and steep MTB downhill trail, I assess the risk, and I ASSESS THE BENEFIT, therefore I am conducting an informal –yet informed by experience– ‘risk benefit analysis’ (RBA). Is it worth it, I’m asking myself; I’m not just doing a risk assessment, because if I only did that, I would tend to want to avoid the risk and stay home under the duvet.

So please, let’s talk about supporting children in their life challenges, and helping them to make wise RBAs. That’s probably an easier sell than ‘risky play’.

9:34 AM

teacher tom said…

I sometimes call it “safety play” because ultimately what the kids are doing is learning how to keep themselves safe, but I’m not yet on board with trying to re-label this sort of play. I mean, people know exactly what we’re talking about, whereas “challenging” might make some people think we are trying to get kids ready for a particularly difficult test or something. Risk is an essential element in this kind of play. I don’t think it’s wrong to talk about it using the words everyone already knows. I’m not calcified in my position or anything, but I don’t want folks to think I’m trying to hide anything. Thanks for offering this point of view: I will be thinking more about it.

8:37 PM

arthur battram said…

“First in a short series of articles about risk, play and policy.

Last month, the Lawson Foundation in Canada announced a new grants programme aimed at ‘getting kids outside and enjoying unstructured, risky play’. This was just the latest example of how the ‘risky play’ banner has been adopted far and wide by advocates aiming to promote giving children greater freedom and more opportunities for adventurous, outdoor play.

But what does ‘risky play’ actually mean? And is its increasingly widespread use to describe one of the primary aims of the play movement, unproblematic? Or is it, in fact, an unnecessarily (ahem) risky strategy, making us hostages to fortune?

In this series of articles, Adrian Voce, who inadvertently had a role in popularising it, will argue that ‘risky play’ is an ambiguous, contradictory term, open to misinterpretation (wilful or otherwise) and that the whole question of how we manage and promote risk is now tending to overshadow and distort some of the wider issues around children’s right to play.”

Tom, meet Adrian…

4:31 AM

===========================================

http://teachertomsblog.blogspot.co.uk/2015/11/safety-play.html

And earlier, if anyone is still reading…

#unlikely

1 comment:

plexity said…

“Increasingly, I find myself bristling when I hear folks talk about “risky play,” even when it’s framed positively. From my experience, this sort of play is objectively not risky, in the sense that those activities like swinging or climbing or playing with long sticks, those things that tend to wear the label of “risky” are more properly viewed as “safety play,” because that’s exactly what the kids are doing: practicing keeping themselves and others safe. It’s almost as if they are engaging in their own, self-correcting safety drills.”

I’ve recently been trying, futilely, to promote the term ‘challenging’ rather than ‘risky’. You’ll appreciate that the the c-word has a double meaning, children are challenging themselves, and adult frettiness is being challenged.

They ARE engaging in their own self correcting activity. I teach playworkers about the ‘edge-of-chaos’ I’ve taken to using hyphens because people confuse it with ‘nearly chaos’. It’s not: edge-of-chaos is an entirely different thing. When I used to do mountain biking it was about finding my personal edge of chaos, my ‘flow state’. We tune to it. Too much and it’s scary, not enough and its boring.

Edge-of-chaos exists in all complex systems, like a group of kids on a playground for example, both as a grip e and for each child.

I loved “catastrophic imaginations.” Spot on.

8:49 AM

Thanks for the edited highlights Arthur (which I had to retrieve from WordPress purgatory). I’d seen some of your comments, though not all. My post started out as a comment on Adrian’s piece, then morphed as it grew. Even so, I get twitchy with posts longer than around 1000 words, so chose not to follow all the lines of thought and comment.

On the substantive issue, I’d like to hear more from practicing educators and playworkers. *Incoming Wittgensteinian alert* these terms don’t simply reside in a Platonic realm. It is through use that meaning and life are breathed into them. Some early years folk whose opinions and practice I respect seem fine with the term ‘risky play’. Teacher Tom seems comfortable-ish with it, though not without his doubts. So I’m not inclined to get overly judgemental.

The Canadian position statement that informs the Lawson Foundation play strategy talks of ‘outdoor play, with its risks’, which I like. If ‘outdoor’ causes problems, than perhaps ‘free play, with its risks’. Still not sure about ‘challenging play’. Though if you pushed me it’d get my vote over ‘adventurous play’.

“Even so, I get twitchy with posts longer than around 1000 words, so chose not to follow all the lines of thought and comment.”

Are you confessing to having a short attention span? You don’t look like a millenial.

Pingback: The R word: risk, uncertainty and the possibili...

Challenging play©Rob Wheway, you should read him.

Rob has a unique take on risk in play. And a unique background in adventure playwork followed by his time at NPFA and his transition to his current role in playground inspection: a rare combination of technical expertise and a forthright playwork ethos. Here’s a sample:

Click to access Surfacing_in_playgrounds.pdf

“LESS RISK MORE ADVENTURE, CHALLENGE AND EXCITEMENT

Whilst not the main theme of this paper I feel it is important to correct some fairly loose thinking around risk which is in danger of promoting “risk” without any beneficial increase in adventure, challenge or excitement. “Children need more risk” is commonly stated however it is a misunderstanding.

If I give an example: those attending Alton Towers type theme parks are invited to ride on “death-defying” rides. Passengers have adventure and excitement, they have the challenge of facing and overcoming real fear but the risks are low. The risks are probably less than driving a car or crossing a road. It would be negligent if the risks were increased.

If a parent wants their child to be able to make a cup of tea before they leave home to get married, they run the risk of the child being scalded. Occasionally people are scarred for life. The benefit of being able to make the tea outweighs the risks. It would be unreasonable and damaging to the development of the child to protect them from this risk.

Kettles have been designed so that there is a reduced risk of them toppling over or dribbling boiling water, electric kettles are designed to avoid the risk of electrocution.

It would be negligent to increase these risks so that scalding or electrocution was more likely on the basis that “children need more risk” and that there would be increased learning from the resultant injuries. There are sufficient opportunities for children to learn that hot water hurts without making it more likely that they will be injured.

Adventure, challenge and excitement are therefore not the same as “more risk“ and there is not necessarily any correlation between them. I believe that we should be ensuring children have opportunities to experience adventure, challenge excitement or simply fun but that we have a duty to reduce unnecessary risk.

What children want from playgrounds is adventure, challenge and excitement NOT an increased risk of injury. The two are not automatically linked.

Well designed equipment can give an impression of danger where risks are low. Some items have a higher risk of being associated with accidents than others e.g. overhead bars. In those cases their popularity, the fun and challenge they present justify the increased risk. They cannot be used without facing that level of risk. The risk is necessary for the enjoyment of the item. The risk can be increased unnecessarily by, for instance, having the child reaching sideways to access the ladder so that they swing sideways which levers open their hands making a rotating fall likely. The risk of injury can also be reduced by having a good impact absorbing surface underneath.

Increased risks with no increased benefits in either adventure or utility should be avoided.”

Rob Wheway MSc. MEd. MCIMSPA. MCMI. FRSA.

Director, Children’s Play Advisory Service

Direct Tel: 024 7650 3540

whewayrob@childrensplayadvisoryservice.org.uk

Pingback: ‘Risky play’: a clarification | Policy for Play

Pingback: La parola R*****O: rischio, incertezza e la possibilità di esiti spiacevoli |

Pingback: La parola R*****O: rischio, incertezza e la possibilità di esiti spiacevoli – Fuori dalla scuola